What Makes a Nativity Scene?

The gospels remind us the story of Christ’s birth isn’t necessary for our salvation. Only our faith in Christ’s saving work for us on the cross is necessary “to transform our humble body that it may be conformed to the body of his glory, by the power that also enables him to make all things subject to himself.” (Philippians 3:21, alternate translation). Mark has no infancy narrative at all, while John’s gospel speaks of the Greek Logos (Word), who is present with God at creation and as co-creator.

Luke and Matthew both have birth stories. Matthew gives us the ancestry of Jesus, the Wise Men or Magi from the East, and the massacre of the innocents. John the Baptist also figures large in Matthew’s text. Luke brings in the shepherds, the host of angels, and the angel’s annunciation to Mary of her impending birth of a savior.

Luke 2:6-7 notes this point about the birth of the Christ child: “While they were there, the time came for her to deliver her child. And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in bands of cloth, and laid him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn.”

This bit of text sets the scene for all the artists of every era to exercise their imagination. What does a first century CE manger look like? What animals would be there? Would the visitors come by day or night? Who would visit a woman who got pregnant while she was still “betrothed?” In every age, gossip travels fast, even without the internet. Traveling traders and business people carried news from town to town.

After all, word had spread how Joseph, “being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss her quietly.” (Matthew 1:19). No wonder there was no room for them at the inn. No respectable place would have them. Or we could be generous to the local folk and say Mary and Joseph travelled slowly because her imminent due date was the cause of frequent stops. A donkey ride might not be the most comfortable ride in one’s late trimester. Either way, if they were late arriving, the rooms may have been booked full already.

The Church of the Nativity, which dates to the 4th CE, was built over the cave in Bethlehem where early Christians believed Christ was born. From Apocryphal sources we learn the traditions of the cave and the stable. The Infancy Gospel of James (chapter 18) also places the Nativity in a cave, but the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew combines the two locations, explaining that on the third day after the birth “Mary went out of the cave and, entering a stable, placed the child in the manger” (chapter 14).

The earliest images of the nativity which currently exist are from 3rd CE sarcophagus panels. The earliest Nativity scene in art was carved into a sarcophagus lid once thought to be for a Roman general, Stilicho, who died in 408 CE. The ox and the ass and two birds are the only figures that appear in addition to Jesus, swaddled in his manger. Our typical cast of characters, including Mary and Joseph, do not appear may be because this sculpture illustrates a prophecy from the Old Testament. Isaiah 1:3 reads, “The ox knows its master, the donkey its owner’s manger…” This Nativity also has relevance to the Eucharist because believers are nourished by the “fodder” of Christ’s flesh, just as the animals receive their sustenance from the manger’s hay. The animals aren’t mentioned in the New Testament, but from the Apocryphal sources mentioned above.

Nativity with Flight to Egypt in the upper part—from the 4th and 5th centuries, Athens, from before the Middle Ages, and technically “Roman” art. (often referred to as “Early Christian”).

Next added were the shepherds, during the 4th and 5th CE, such as this example from the Palazzo Massimo. We find it on the sarcophagus Marcus Claudianus, on the upper tier, on the left. This dates from around 350 CE, found today in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome.

The sculptor carved the sarcophagus in the style called “continuous frieze” because all the figures line up and their heads are of equal height. The appearance of grape harvest imagery on the lid is ambiguous; it appears on both pagan/secular and Christian sarcophagi with identical elements. From left to right on the lid: nativity scene of Jesus, sacrifice of Isaac, an inscription naming the deceased, an image of the deceased as scholar, and a grape harvest scene.

Carvings on the front of the Marcus Claudianus sarcophagus include: Arrest of Peter, miracle of water and wine (with a possible baptism reference), an orant or praying figure, miracle of loaves, healing a man born blind, prediction of Peter’s denial, resurrection of Lazarus and supplication of Lazarus’ sister.

A Carolingian Era (751-887) Nativity scene from the British Museum

Eastern Orthodox icons retain the cave imagery while the Western art traditions use a stable or ruins of a classical structure in the nativity scenes. The first is according to tradition and the western imagery reminds the viewer the ancient past with its many gods is no longer ascendant.

The one change we see in the 6th century is the inclusion of Mary lying on a mattress type bed. It may have appeared earlier in art, but we have no surviving example to date an earlier occurrence. Later, we see more actors in the drama appearing, but often they don’t arrive all at once. The wise men visit, or the shepherds visit, but not in the same artwork.

things changed much more slowly in the Middle Ages than they do now.

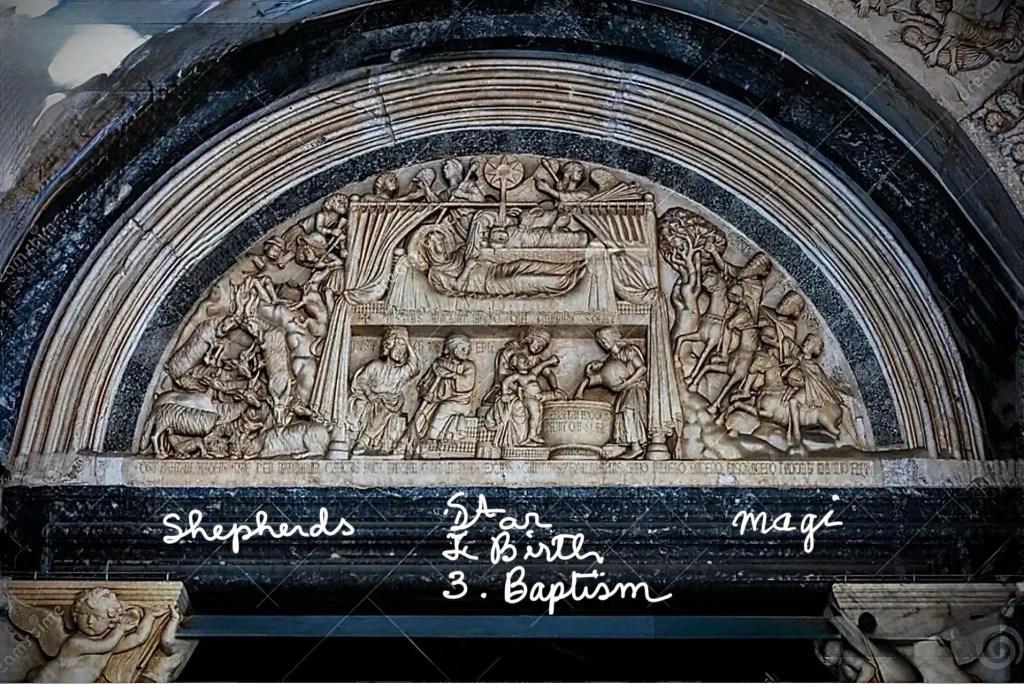

By the time of the 11th CE, the nativity scene was becoming more elaborate , but was not yet in full flower. By the 13th CE, the magnificent portal of the St. Lawrence cathedral, in Trogir, Croatia, by the Master Radovan and his associates has a strong narrative of the many parts of the nativity story. The city of Trogir, a World Heritage Site since 1997, is known as one of the best-preserved Romanesque-Gothic cities, the core of which consists of forts, religious and secular buildings, with the Rector’s Palace and the City Loggia standing out. Its Romanesque churches are supplemented with Renaissance and Baroque edifices.

The detail of the portal is worth a closer look. In the center, in between the curtained “bunkbeds,” the Virgin and Child rest on the upper tier. The animals also look on in this section. Below the manger scene is a ritual bath. In my Christian world view, I called this the “baptism of Jesus.” In his Hebrew life, he would have undergone a ritual cleansing immersion bath before going to the temple for his circumcision. This ritual would mark him as a covenant member of the nation and people of God. The two elderly people on the left of this scene are most likely Simeon and Anna, prophets who speak to the child’s fulfillment of scripture.

Above all this at the center top are the star, with the angels on the left and on the right. Filling the space on the left side of the portal are the shepherds and their herds, while the Magi and their steeds occupy the right side. The Magi ride horses, unlike our modern nativities which have camels.

In England, the Venerable Bede (d. 735) wrote the Magi were symbols of the three parts of the world—Asia, Africa, and Europe. They signified the three sons of Noah, who fathered the races of these three continents (Genesis, chapter 10). By the late Middle Ages, this idea found expression in art, and artists began to depict one of the kings as a black African. The kings sometimes have their retinues, which include animals from their presumed places of origin: camels, horses, and elephants are the most common. As with the shepherds, the artists often represented the three kings in the various stages of life: young, middle aged, and old age.

Artists added more exotic animals to the nativity scenes in the 15th CE when trade and travel were expanding beyond the continent. Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi (painted in 1423) presents a remarkable range of animals. Alongside the traditional ox, donkey, sheep (and a couple of dogs thrown in for good measure), the chaotic scene includes a camel, cheetah (or leopard), hawks and monkeys.

Engraving from Ferrante Imperato, Dell’Historia Naturale (Naples 1599)

The inclusion of animals which were not native to Europe helped Gentile da Fabriano to emphasize the three wise men’s journey from the Far East, but also to impress viewers with its exoticism and visual richness. This would have reflected very well on the painting’s patron, the rich Florentine banker Palla Strozzi, as it reinforced his connections to foreign lands. In this era, many rich citizens had a collection of exotic animals and imported wares, just as wealthy people today have collections of art, yachts, or sports cars to showcase their riches.

An even more elaborate nativity comes from the hand of Botticelli, who worked in the wealthy merchant city of Florence, Italy, in 1500. Savonarola was a fanatical preacher who aimed to morally reform the city of Florence, which had a global reputation for artistic output and lavish lifestyles. Savonarola condemned secular art and literature, decried the city as a corrupt and vice-ridden place bloated with material wealth, and, after warning of a great scourge approaching, saved the Florentines by convincing the French king and military to deoccupy and recede during the Italian War of 1494–98.

The people thought of him as a prophet and came from miles around just to hear him preach his apocalyptic message. He preached a sermon telling the people of Florence they could become the new Jerusalem “if only its civilians would part with and burn their luxuries, opulent fineries, and give up their pagan or secular iconographies.”

Botticelli fell under Savonarola’s influence during this time, for his art changed from decorative to religious. The 12 angels at the base of the composition each hold a ribbon that the artist inscribed with the 12 privileges or virtues of the Virgin Mary, which came from a sermon Savonarola delivered about a vision he once experienced. Another unusual aspect is that the three kings welcome Jesus empty-handed, rather than with gold, frankincense, and myrrh — influenced by Savonarola’s sermon, though it could be their ultimate gifts are their prayers and devotion.

Sometimes it’s impossible to know whether the artist was inspired by a non-biblical element or by an apocryphal text in a Nativity scene or if the artistic depiction came first. In their book, Art and the Christian Apocrypha, David R. Cartlidge and J. Keith Elliott contend in the making of early Christian art, written and visual sources are interdependent. “The developing consensus is that oral traditions, texts (rhetorical arts) and the pictorial arts all interact so that all the arts demonstrate the church’s ‘thinking out loud’ in both rhetorical and pictorial images” (2001, xv).

When we artists imagine the nativity today, we add to the basic scripture text all of the Hollywood movies we’ve seen, the stories we’ve heard around the fireplaces and altars of our instruction, and every Christmas card and artwork we’ve ever seen. Our memories of Christmas are often more important than Christmas itself. This is because we have an idea of how Christmas is supposed to BE, but the birth of Christ wasn’t what either Mary or Joseph thought it was going to be. Just as most of us, they hoped to be at home and near family, not “away in a manger, no crib for a bed.”

God brought the Savior of all into our world into a humble setting, not to a royal palace. God brought to the birthplace of Christ strangers from distant lands and marginalized people from their homeland to have the first opportunity to worship the newborn king. God excluded the political rulers because they were out to destroy this unusual king.

We are part of the Christian community now, so we sometimes miss the disruptive nature of Christ’s birth. As part of the in/dominant group today, we might have a tough time reading the Bible’s challenges to self-satisfaction and complacency.

We often forget while these depictions of the Nativity were evolving, the segment of the Roman Empire that was still pagan were also representing famous births, that predate the standard depictions of the Nativity of Christ. For example, in a Roman villa near Baalbek, Lebanon a fourth century mosaic of the Birth of Alexander the Great at first sight almost exactly resembles what later became a standard depiction of the Nativity of Christ. This mosaic, today in the National Museum of Beirut, shows the newborn Alexander the Great being bathed in a circular fluted basin by a female figure labelled ‘Nymphe’, while his mother Olympias reclines on a bed watched by an attendant.

Compare this with the icon of the Wise Men Visiting the Birth of Christ, from the 6th CE pictured above. In the lower right corner of this nativity scene, we see a small depiction of the Christ child being bathed, with water being poured over his head. (Obviously a United Methodist, but a precursor since John Wesley wasn’t born yet!) Our Christian iconography is derived from pagan sources. By this I mean we reimagined the pagan iconography and repurposed it for our own spiritual practices and purposes.

One of our other challenges is the calendar. We in the West use the Gregorian calendar, from the 16th CE, while the Orthodox Church still follows the Julian calendar, which was in use during the time of Christ. This is why the Orthodox community still celebrates Christmas and Easter on different dates than the Western churches. In the Orthodox Church, they celebrate Epiphany as the baptism of Jesus rather than the arrival of the Magi (Three wise men), which the Western Church celebrates on 6 January. On the Gregorian calendar, this Orthodox Epiphany celebration is January 19th. They celebrate this date as the Baptism of Jesus, rather than the arrival of the wise men. Their Epiphany is located in the baptism rather than the nativity. That’s a whole other theological discussion beyond the iconography of the nativity!

I mention this fact of the two calendars because I’m always “calendar challenged.” It’s not a senior citizen thing, because this was my problem even when I was in my twenties also. Sometimes I put too many commitments on my calendar, and other times I underestimate the time to complete my tasks. Then again, there’s always the unexpected interruptions. Always the interruptions. I came to understand in my ministry my list of tasks to do were not my actual work, but instead these interruptions were the opportunities which God would bring to me to do God’s chosen ministry.

So, I’m a few days late on the Western calendar for the visit of the Three Kings, having missed January 6th, and I’m a few days early for the Orthodox calendar. As Goldilocks said, “Not too hot, not too cold, but just right!”

The last art pieces our class made in 2024 before the holidays and the snowstorms were our nativity paintings. I asked each person to use their imagination and to bring the essence of the nativity to their creative process. Some of us quickly realized our images and used our second meeting to do a personal project or another version of the nativity scene. Others of us took both sessions to perfect our one image. I blame the Christmas cookies and our lack of hand and mouth coordination. Sometimes it’s hard to chew and paint at the same time!

Our first class of 2025 was an instance of “calendar challenge”—I thought we were having it, but the group didn’t. The next week, a major snow storm canceled class every where for everyone. Friday, January 17, should be a good day to begin a new project! We’re going to do some mixed media, along with weaving projects in the days and weeks to come. You don’t need skills, but a willingness to try.

Joy, peace, and a hope for better weather!

Cornelia

The Nativity Tympanum on the Sarcophagus of Stilicho

https://www.christianiconography.info/Wikimedia%20Commons/nativitySarcophagusStilicho.html

UNESCO monuments in the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts Glyptotheque

https://gliptoteka.hazu.hr/unesco/en/trogir.html

The Apocryphal Gospels—PseudoMatthew—has Latin text and translation

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Apocryphal_Gospels/Cmbtm4ZZXF0C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=M.+Berthold+has+argued+that+Pseudo-Matthew&pg=PA75&printsec=frontcover

The Infancy Gospel of James (2nd century) |http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf08.vii.iv.html

The Arabic Infancy Gospel (5th-6th century) http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf08.vii.xi.html

The Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew (8th or 9th century) http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf08.vii.v.i.html

Web Gallery of Art, searchable fine arts image database

https://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/support/zearly/1/1sculptu/sarcopha/1/9claudi2.html

Nativity – Visual Elements in the Nativity — Glencairn Museum

https://www.glencairnmuseum.org/nativity-visualelements

Johann International: Search results for Nativity http://johanninternational.blogspot.com/search?q=Nativity

Revisiting Botticelli’s Evocative “Mystic Nativity” https://hyperallergic.com/978201/revisiting-botticelli-evocative-mystic-nativity/

ORTHODOX CHRISTIANITY THEN AND NOW: Origins of the Icon of the Nativity of Christ

https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2018/12/origins-of-icon-of-nativity-of-christ.html

Leave a comment