-

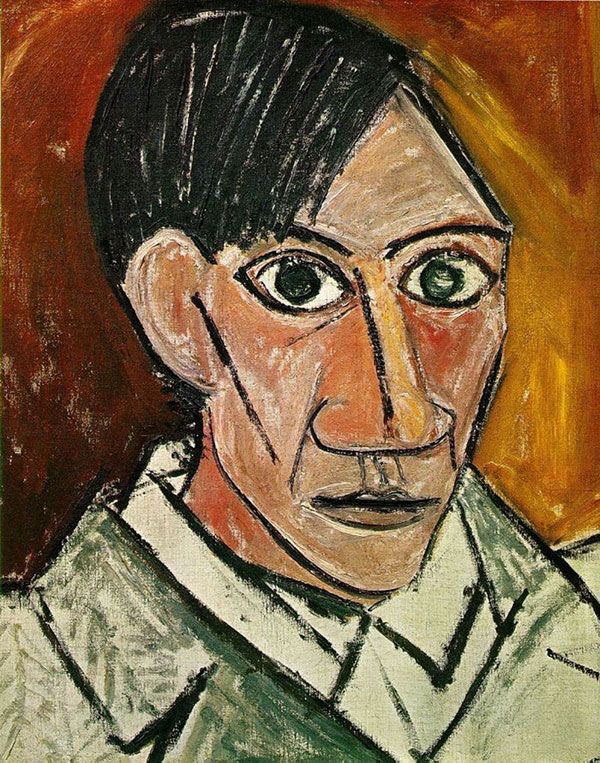

Picasso’s African Masks and Inner Mysteries

What is the key to open the door to the hidden mysteries? For Frodo and his fellow travelers in The Lord of the Rings trilogy, they needed to know the elvish answer to the riddle, “Speak friend and enter.” Gandalf knows this language, so they enter with ease. For years, the Egyptian hieroglyphics were unintelligible…

-

Rabbit! Rabbit!

Welcome to August! In the long summer evenings, after an extended car trip, and way beyond the too many times I’d asked my mother and daddy rabbits, “Are we there yet?” I would get their firm reminders I wasn’t to bother them any more, for they too were hot, tired, and daddy had to pay…

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.