The 2026 snowpocalypse known as Winter Storm Fern has come and gone, at least for the southern states. As I’m writing this, a lone lump of ice remains under the shade of the collapsed carport next to the barbecue area of our condominium complex. I returned from exercising and sat down to visit with the usual suspects, the men who love to light the fires and cook outside. We visited for a while in the afternoon sunshine, which is what neighbors do, especially those of us who just spent the week and a half indoors. Because we are on the lake, access to our building is uphill. This means the exit to the highway is a downhill side street, shaded and unplowed. No one went anywhere anytime fast. At least we didn’t lose power, as some did. For this we are thankful.

By the time art class rolled around, we were still locked uptight. I canceled that class because I would not want to risk people’s lives just for art class. We don’t save anyone’s life here in art class, but we do improve everyone’s wellbeing. Missing one class time won’t do a great harm to us. I let everyone know, “Bring an image of snow to paint from next week.” We were all glad to be out and about once again.

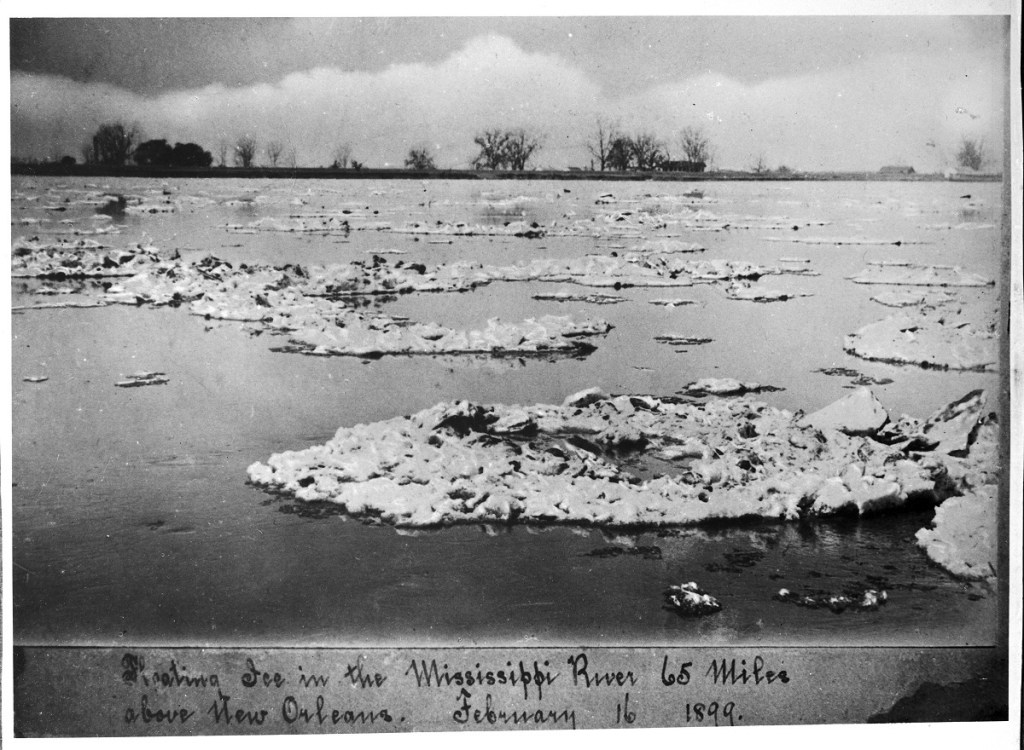

Of course, we’re all glad we aren’t living in 1899 during the Great Valentine’s Day blizzard. It began as a Saskatchewan Screamer and lasted over two weeks. It covered not only the entire continental United States but also spread as far south as Cuba! The National Weather Service recorded temperatures on February 12th below freezing for Little Rock (-12 F) and for Fort Smith (-15). Springfield, MO shivered at minus 29F, while Camp Clark, NE was frozen solid at minus 47F. This cold snap even caused mini-icebergs on the Mississippi River. New Orleans had four inches of snow between February 12 and Valentine’s Day, a blizzard for this southern city. Coming just days before Mardi Gras, it covered the French Quarter streets with ice and snow. The temperature never got above 30F, so 1899 was the coldest and least comfortable parade ever.

As children, we are thrilled to have snow days, but our grown ups will “groan and moan” after just a few hours of “imprisonment.” Itching to get out, some will throw caution to the wind and venture out on icy roads without snow tires or chains. I’ve driven over the continental divide in a driving snowstorm, but at least I had the good sense to follow a semi truck, which was driven by a professional driver. He knew fifteen miles per hour would bring us all home in one piece and we’d live to tell the tale one day years later. This is how people in the mountains get places—they depend on each other, for going out alone in a storm is asking for trouble.

Even Florida had its coldest temperature ever recorded: -2F in Tallahassee on February 13, 1899, during this historic Arctic outbreak. People had snowball fights on the steps of the city buildings in Tallahassee. The sharp cold front that ushered in the record-setting chill didn’t stop after sweeping across the U.S. Intense waves crashed into Cuba’s coastline as the cold front stirred up rough seas and washed away some buildings near the beaches. While this storm over a century ago lasted longer than our more recent one, we did break one record this year: Little Rock recorded 6.0 inches of snow in one day, shattering the earlier daily record for snowfall of 4.0 inches set back in 1899.

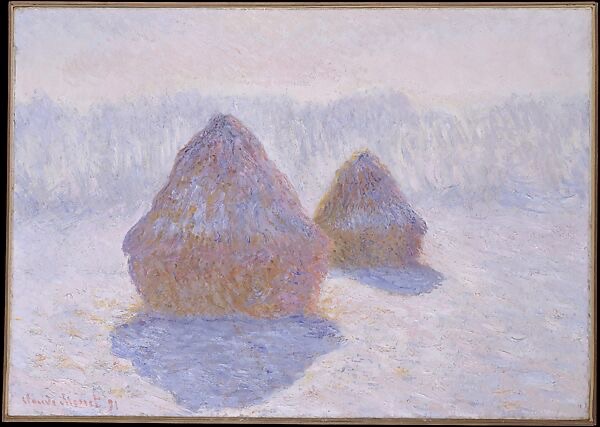

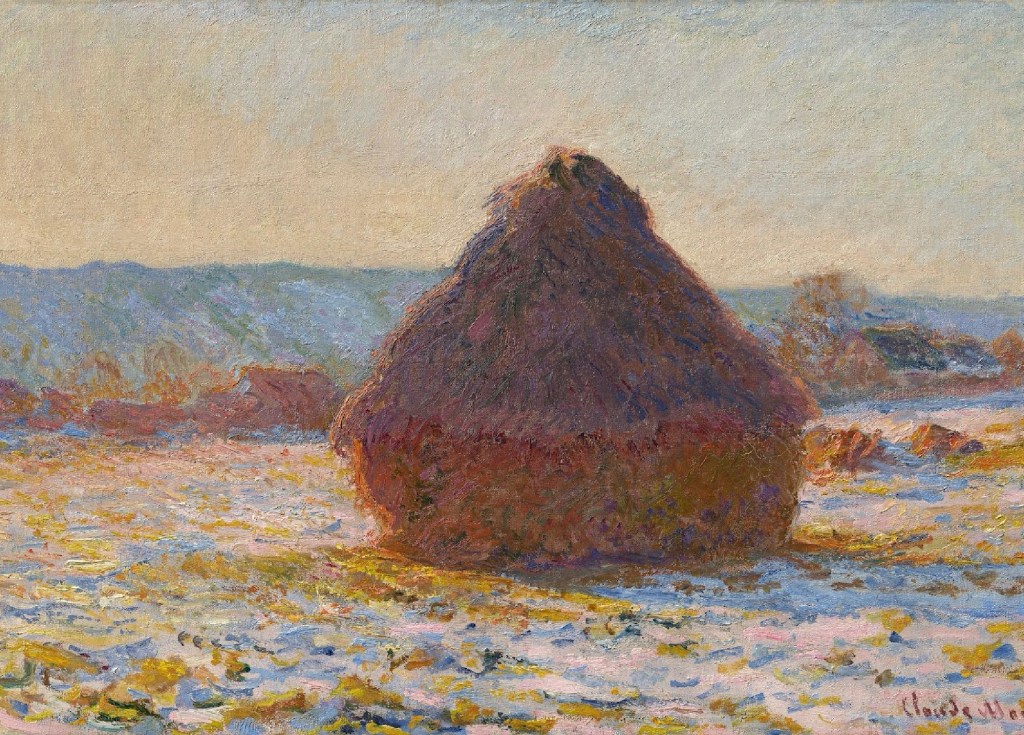

The world is beautiful, however, and it attracts artists to paint the changing light upon the snow-covered landscape. Claude Monet painted thirty works of grain stacks in winter weather to examine the seasonal change of the landscape and the varying influence of sunlight according to the time of day. He captured the characteristic mood of the light on a cold winter’s day and described the reflections on the snow-covered field in delicate tones of yellow and orange. After beginning outdoors, Monet reworked each painting in his studio to create the color harmonies that unify each canvas. The pinks in the sky echo the snow’s reflections, and the blues of the wheat stacks’ shadows are found in the wintry light shining on the stacks, in the houses’ roofs, and in the snowy earth.

All the colors of our world change when our environment is snow-covered. If we pose a person next to a brick wall, their face takes on a ruddy tone. If we set them next to a pale blue curtain, their facial color will tend to pale. Likewise, setting someone in the sunshine will give them a healthy glow. In landscapes, we note how the water reflects the color of the sky or the overhanging foliage. A stormy sky has a gray sea, just as a sunny sky has a deep blue or turquoise sea. With snow, the white ground picks up the colors of the sky and sunlight, as well as the colors of the buildings and growing things. Shadows are of varying colors, depending on the time of day and the objects that cast them.

Most of the time, we paint the snow in browns and grays, just as the early Paul Gauguin, Garden Under the Snow. We haven’t learned to see the colors of a Monet or the island Gauguin. We see only what is on the surface, rather than observing and discerning the true colors hidden beneath.

Monet had a fine eye which was further honed by patient observation. As he said about his technique:

“When I began I was like the others; I believed that two canvases would suffice, one for grey weather and one for sun. At that time I was painting some haystacks that had excited me and that made a magnificent group, just two steps from here. One day, I saw that my lighting had changed. I said to my stepdaughter: “Go to the house, if you don’t mind, and bring me another canvas!” She brought it to me, but a short time afterward it was again different:” Another! Still another!” And I worked on each one only when I had my effect, that’s all. It’s not very difficult to understand.’”

Of course, this is why we look at the great masters of old: they teach us even if we don’t at first appear to have absorbed the lessons from them. Looking at great art works is like a farmer planting a seed. The farmer doesn’t expect to eat bread the next day! A grain takes time to sprout and mature. The farmer feeds it and cuts out the destructive weeds. My memories of art school “feeding” sometimes felt like “manure heaping.” Teachers were rough on those who had promise, they said. I taught differently—I would find three positive aspects of a student’s work before I spoke about anything I thought needed improvement. Never would I call a work bad, for too many people have their self worth bound up in what they do or create.

Mike got a good start on his snow scene, but had to leave early. He planned to use blue watercolor for the sky instead of acrylic paint. This makes his choice to add the tiny leaves on the right-side trees acceptable. Otherwise, if he were painting the sky in acrylic paints, he would have painted it first and then added the trees. Sometimes we have to plan before we paint.

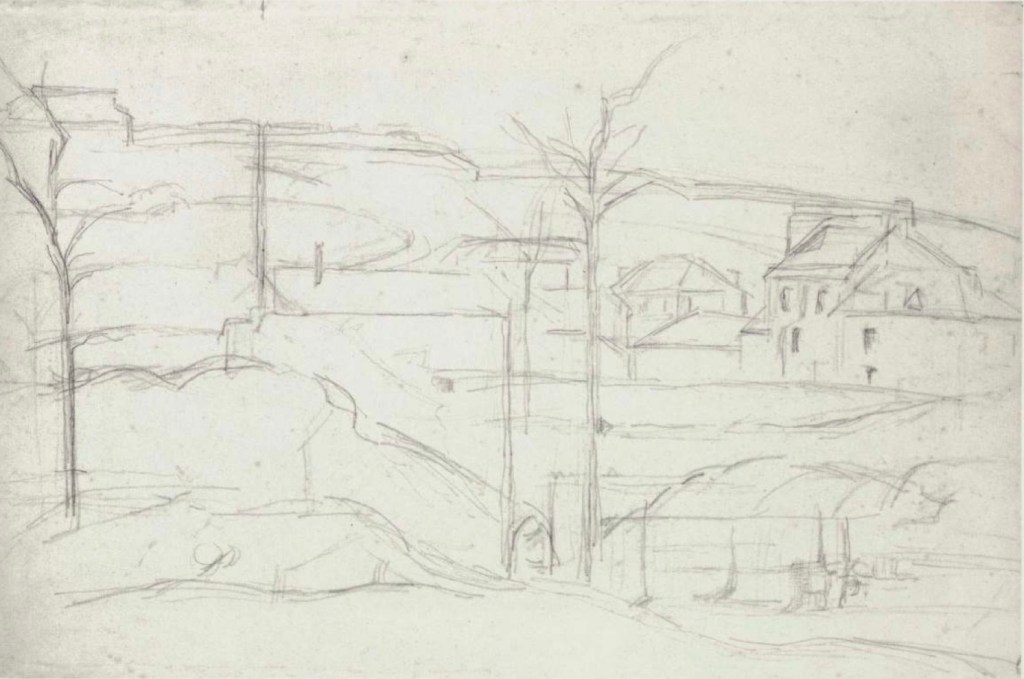

Gail was working from a photograph of a snow covered bush from her garden. The shadow shapes are as interesting as the bush itself. The strong diagonals are a bold design choice. Our short painting period didn’t let her paint in the fence area of the background. Sometimes we struggle to match a shape or line we see, rather than letting go and drawing what we think approximates it. Cezanne was well known for this multiple line technique, while Matisse drew a single line, as did Picasso.

All three are renowned artists, and no one discounts Cezanne for using many lines while the later use only one. We call this “style.” We have to let go of the perfect and accept the good. Somewhere among the good lines is a better line which we can emphasize. With acrylic paint, we can then hide the former lines, and no one will know the difference. When we allow ourselves to work more freely, we will find a new lyricism in our work.

I worked from a photograph taken several years ago by one of my young friends—who am I kidding—any friend I have is young! He got out into the snow-covered streets in the downtown Hot Springs historic district. The combination of the electric lights and the natural lights cast varied colors of shadows on the snow. The simple one-point perspective ties the whole together by bringing the viewer’s eye to the approximate center of the painting. The varied colors are then brought into a focal point to calm the eye. Thus the painting has both tension and calm at the same time.

Japanese artists handle the mists of snow falling using ink and washes. A beautiful three-part screen from the 16th CE in the Tokyo Museum of National Art shows pine trees partially obscured by falling snow. I can just imagine Hasegawa Touhaku sitting inside an ancient temple or a home of great antiquity. Warmed by a small charcoal brazier, he spread his paper out upon grass mats. Grinding his ink on a stone, he watered it down to a thin solution and began to paint. First the lightest tones, for the soft flakes of snow falling soften the structures of the trees in the distance.

Then he added more ink to the liquid, grinding the ink stick smaller as he contemplated the shape and placement of the next trees. Some are placed directly over the background trees, then he paints other trees with darker ink yet, representing trees closest to the viewer. Most importantly, he leaves most of the triple screen blank, for the falling snow effect. At the last moment, only the central set of trees has a few marks at their base to denote rocks or ground. The rest of the screen is “snow-covered.”

Each one of these famous artists can teach us how to see. Vincent Van Gogh reminds us, “Paintings have a life of their own that originate in the soul of the artist.” If we try to have empathy with the artist who made the work, or find common experience with the subject painted, we can then begin to learn from the work of art. If we treat the artwork as a consumable object, like a hamburger or a soda pop, it won’t move us at all, nor will it teach us any of its secrets. As Leonardo da Vinci said, “There are three classes of people: Those who see. Those who see when they are shown. Those who do not see.”

As a teacher, my calling is to help people see. Seeing is a form of mindfulness. Looking slowly, taking our time to observe nuances, and even letting the object or the landscape look at us means we begin to know it better. If we rush to make decisions, we define what we think it should be, rather than waiting for the subject to tell us what it truly is. We sometimes judge books by their covers, or people by their outward appearances. As we read in 1 Samuel 16:7—

But the LORD said to Samuel, “Do not look on his appearance or on the height of his stature, because I have rejected him; for the LORD does not see as mortals see; they look on the outward appearance, but the LORD looks on the heart.”

Leonardo’s advice for the “Principles for the Development of a Complete Mind” bears true for our age also: “Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses — especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

This is mindfulness: to see with the heart and eyes of God, not with only our human eyes and hearts. To love and wonder at all creation, and to care for all. This is “having the mind of Christ,” who is the image and likeness of God. I rejoice we’ve said goodbye to the snow and will enjoy a little joy of hearts for Valentine’s Day before we set out on our Lenten Journey. Ash Wednesday is is February 18th, so the Friday following we will do a cross oriented project. The days are getting longer, so I hope we are all feeling a bit more “spring in our step.” It’s never too late to begin a new adventure, so you can join us at 10 am on Fridays at Oaklawn UMC for art class.

Joy and peace,

Cornelia

Great Arctic Outbreak of 1899

https://www.weather.gov/media/bro/research/pdf/Great_Arctic_Outbreak_1899.pdf

Florida hits 112-year record low temperature – Newsweek

https://www.newsweek.com/florida-hits-coldest-temperature-in-over-110-years-11032525

“Land of the Defunct Orange Tree and Ice-Burdened Palmetto” – 64 Parishes

https://64parishes.org/land-of-the-defunct-orange-tree-and-ice-burdened-palmetto

Break-up of the ice on the Seine, near Bennecourt | National Museums Liverpool

https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/break-of-ice-seine-near-bennecourt

Leave a comment